The Trouble With Modern Monetary Theory

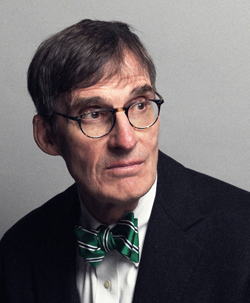

Jim Grant

Modern monetary theory is not so theoretical anymore. In all but name, it’s the description of Republican fiscal policy in this living moment. “Federal Borrowing Soars as Deficit Fear Fades,” said the headline on page one of Tuesday’s Wall Street Journal. For the second year in a row, the Trump administration is spending $1 trillion more than the government expects to extract from the taxpayers. Modern monetary theory is not so theoretical anymore. In all but name, it’s the description of Republican fiscal policy in this living moment. “Federal Borrowing Soars as Deficit Fear Fades,” said the headline on page one of Tuesday’s Wall Street Journal. For the second year in a row, the Trump administration is spending $1 trillion more than the government expects to extract from the taxpayers.

The Bourgeois Gentleman is the Molière play in which a character comes to the proud realization that he has been speaking prose all his life without even knowing it. By the same token, the Trump administration has been implementing the essential doctrines of “functional finance,” also known as MMT, without seeming to realize it.

No harm came to Molière’s character, M. Jourdain, for his funny lack of self-awareness. The stakes are higher for all who live under the influence of the 20th-century progenitor of MMT, the economist Abba Lerner.

You can boil down MMT, as James Montier did in Barron’s last week, to a few handy precepts. The first is that money is the government’s creation, not society’s. It derives its value from the fact that you can pay your taxes with it.

Right away, you understand the political foundation of the body of ideas associated with Lerner, an avowed Marxist. But MMT is a big tent, and there’s plenty of room for Republicans.

“[W]hatever may have been the history of gold,” Lerner wrote in 1947, “at the present time, in a normally well-working economy, money is a creature of the state. Its general acceptability, which is its all-important attribute, stands or falls by its acceptability by the state.”

President Donald Trump has never put it exactly that way, but Lerner’s idea is implicit in the way 21st-century central banks do business. They set interest rates and print money to achieve prosperity—full employment, as Lerner defined it; full employment plus record-high stock prices, for Republicans. Borrow money, spend it, materialize it out of thin air, Lerner counseled. Stop when economic growth reaches its physical constraints of spare labor and capital. If inflation accelerates, lower the boom by taxing the rich instead of borrowing from them. Except for the admonition to tax, the White House and Lerner are on the same page.

The second big idea in MMT concerns the nature of the public debt. There’s nothing to fear from it, said Lerner - at least, not if a government can borrow indefinitely in its own currency.

“The greater the national debt,” the economist wrote, “the greater is the quantity of private wealth. The reason for this is simply that for every dollar of debt owed by the government, there is a private creditor who owns the government obligations...and who regards these obligations as part of his private fortune.”

Lerner carried the argument to its logical Keynesian conclusion: The greater our collective fortune, the less we need to save. The lower our savings, the greater our spending. The greater our spending, the higher the level of our employment.

The Trump White House talks an orthodox fiscal game, even now; Lerner made no such pretense, believing as he did that the public’s liabilities are identical to the public’s assets. We owe it to ourselves, in other words—and, of course, nowadays, to the foreign bondholders, too.

Lerner was a close reasoner and lucid writer. In his carefully constructed theoretical world, the public debt would not grow indefinitely but rather tend to melt away. Why?

“The greater the national debt, the greater is the quantity of private wealth” and, hence, the lower the need to borrow.

It has not worked out quite that way. Famously, the debt has not melted away, but spurted. In the past 20 years, the ratio of federal debt to gross domestic product has leapt to 105% from 60%. Over the same two decades, observe Van Hoisington and Lacy H. Hunt, guiding lights at Hoisington Investment Management, in Austin, Texas, GDP has grown at 1.2% a year per capita, 37% below the long-term U.S. average.

Lerner failed to anticipate today’s looming entitlements crisis, the falling national birthrate, and the striking decline in the rate of private saving these past 10 post-crisis years.

The empirical fact, again to draw on Hoisington and Hunt, is that “large indebtedness eventually slows economic growth as resources are transferred from the highly productive private sector to the government sector.”

“We have, indeed, been told that the public is no weaker upon account of its debts,” wrote an earlier commentator, “since they are mostly due among ourselves, and bring as much property to one as they take from another. It’s like transferring money from the right hand to the left; which leaves the person neither richer nor poorer than before.”

That was David Hume, Scottish philosopher and contemporary of Adam Smith, writing in 1777.

Anticipating MMT in an essay entitled “Of Public Credit,” Hume called it “buncombe.”

In fairness to MMT, England did not default, as Hume feared it would, and as American patriots, then fighting the Revolutionary War, hoped it would. In fairness to Hume, many another nation did subsequently default. Indeed, in 1933 and 1971, the U.S. itself left its creditors high and dry by refusing to honor its promise to pay dollars denominated in a fixed weight of bullion.

Now that dollars are fashioned from paper or (an even lighter-weight material) digital keystrokes, formal default is unnecessary. The government can print whatever it needs to service its fixed charges. The question is whether the creditors will cheerfully accept the currency so effortlessly tossed off the 21st-century presses.

Hume, steeped in the classics, reminded his readers that Roman emperors stored up treasure against some future day of peril.

The “modern” expedient, Hume disapprovingly continued, “is to mortgage the public revenues, and to trust that posterity will pay off the encumbrances contracted by their ancestors: and they, having before their eyes so good an example of their wise fathers, have the same prudent reliance on their posterity; who, at last, from necessity more than choice, are obliged to place the same confidence in a new posterity.”

Speaking for the newest posterity - that’s us - I have arrived at one certain conclusion: The word “modern,” written or spoken in the fiscal, monetary, or financial context, is trouble - nothing but trouble.

James Grant was born in 1946, the year interest rates put in their mid-20th century lows. He founded Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, a twice-monthly journal of the financial markets, in 1983, two years after interest rates recorded their modern-day highs.

Born in New York City and raised on Long Island, he had thoughts, first, of a career in music, not interest rates—french horn was his love. But he threw it over to enter the Navy. Following enlisted service aboard the U.S.S. Hornet, and, as a newly minted, 20-year-old civilian, on the bond desk of McDonnell & Co., he enrolled at Indiana University. There he studied economics under Scott Gordon and Elmus Wicker and diplomatic history under Robert H. Ferrell. He graduated, Phi Beta Kappa, with a Bachelor of Arts degree in economics in 1970. Next came two happily unstructured years at Columbia University that produced a master’s degree in something called international affairs but, more importantly, the privilege of studying under the cultural historian, critic and public intellectual Jacques Barzun.

In 1972, at the age of 26, Grant landed his first real job, as a cub reporter at the Baltimore Sun. There he met his future wife, Patricia Kavanagh, and discovered a calling in financial journalism. It seemed that nobody else wanted to work in business news. Grant served an apprenticeship under the longsuffering financial editor, Jesse Glasgow. He moved to Barron’s in 1975.

The late 1970s were years of inflation, monetary disorder and upheaval in the interest-rate markets—in short, of journalistic opportunity. It happened that the job of covering bonds, the Federal Reserve and related topics was vacant. In the mainly placid years of the 1950s and 1960s, those subjects had seemed too dull to care about. But now they were supremely important—even interesting—and the editor of Barron’s, Robert M. Bleiberg, tapped Grant to originate a column devoted to interest rates. This weekly department, called “Current Yield,” he wrote until the time he left to found the eponymous Interest Rate Observer in the summer of 1983.

Grant’s books include three financial histories, a pair of collections of Grant’s articles and three biographies. The titles are these: “Money of the Mind” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1992), “The Trouble with Prosperity” (Times Books, 1996) “Minding Mr. Market” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1993), “Mr. Market Miscalculates” (Axios Press, 2008) and “The Forgotten Depression, 1921: the Crash that Cured Itself” (Simon & Schuster, 2014), which won the 2015 Hayek Prize of the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research.

Also, “Bernard M. Baruch: The Adventures of a Wall Street Legend” (Simon & Schuster, 1983), “John Adams: Party of One” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2005) and Mr. Speaker! The Life and Times of Thomas B. Reed, the Man Who Broke the Filibuster” (Simon & Schuster, 2011).

Grant’s television appearances include “60 Minutes,” “The Charlie Rose Show,” Deirdre Bolton’s “Money Moves” program on Bloomberg TV and a 10-year stint on "Wall Street Week". His journalism has appeared in a variety of periodicals, including the Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal and Foreign Affairs, and he contributed an essay to the Sixth Edition of Graham and Dodd's “Security Analysis” (McGraw-Hill, 2009).

Grant is a 2013 inductee into the Fixed Income Analysts Society Hall of Fame. He is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and a trustee of the New-York Historical Society.

He and his wife live in Brooklyn. They are the parents of four grown children.

goldsilver.com

|