Send this article to a friend:

June

02

2018

Send this article to a friend: June |

|

How silver changed the world

It can be argued that when Spain instituted a common currency in the form of the Real de a Ocho, also known as Pieces of Eight, or the Spanish dollar, globalisation’s first chapter had been written. The acceptance of the dollar coins for commercial transactions throughout Asia, the Americas and much of Europe, resulted in a cultural exchange between nations, as well as the relatively free movement of people and goods between the three continents Global trade China had an appetite for silver ...When the Spanish tried to establish commercial ties with China they found little taste for goods from the outside world. However, it transpired the Chinese had a voracious appetite for silver. In fact, during the latter part of the 16th century, during the Ming Dynasty, Beijing ruled taxes should be paid in silver, and without domestic recourse to the precious metal, the demand for imported silver soared.

Cerro Rico, Potosi Spain’s colonies in the Americas could mine enormous quantities of silver and the Spanish began to export the commodity to China via their Manila connection. The colonial mint was located in the Bolivian city, Potosí, for several centuries. At an altitude of 4,000m, Potosí lies at the foot of the Cerro de Potosi, a mountain popularly conceived as being made of silver ore. China’s insatiable demand for silver led to increased production in the Bolivian highlands and by the late 16th century Cerro de Potosi alone produced an estimated 60 per cent of all silver mined in the world. … while the West hungered for goods from China. Many of the products imported into New Spain were highly coveted luxury goods. Silk was popular, both in its raw form and finely embroidered, as was porcelain, diamonds, pearls, ivory and wooden furniture. Cotton from the Philippines, and other parts of Asia, became highly profitable due to the high quality. Other products in demand were spices, tea, Indian linen, amber, swords and knives, potassium nitrate for gunpowder, and mercury, for industrial use to mine silver Manila as central hub of Asia Over the years, Chinese commercial vessels began to arrive in Manila with increasing regularity

Junks and other small boats sail between March and June to avoid typhoon season and the southwest monsoon rains Manila was ideally located as a major trading port for Chinese goods which were highly coveted in Europe and America. The Chinese community in Manila grew exponentially to keep pace with the booming trade. Manila also provided sailors with respite before their long and arduous journey to Acapulco, the Spanish base where galleons would unload and trade their goods for silver ingots, and later, coins

The Manila Parian, Philippines Manila was ideally located as a major trading port for Chinese goods which were highly coveted in Europe and America. The Chinese community in Manila grew exponentially to keep pace with the booming trade. Manila also provided sailors with respite before their long and arduous journey to Acapulco, the Spanish base where galleons would unload and trade their goods for silver ingots, and later, coins

The Chinese who left their ships to settle in Manila often set up shop as traders. Many of the Chinese merchants in Manila took residence in an area adjacent to the Intramuros – a walled city hosting most of the Spanish colonial and administrative buildings. Known as Parián, this area quickly became the commercial centre of Manila. There were over a hundred shops prospering, and it was here that products arriving by junk from China were traded. Chinese who converted to Christianity (called sangleyes by the Spanish) were able to expand their business interests to other provinces in the Philippine islands Growth of Manila’s Chinese population

Over the years Manila’s population became one of the most diverse in the world, with people settling there from Spain, France, England, Italy, Flanders, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Poland, Russia, Turkey, Greece, Persia, Africa, as well as Tartars, Chinese, Japanese and others from across Asia. Acapulco and Mexico City New Spain, especially Acapulco and Mexico City, began to depend on the China Ships for the open trade route. When galleons arrived in Acapulco they were greeted with much festive activity. There were joyful celebrations starting with Mass and followed with parties and market fairs.

Most of the goods arriving in the China Ships were transported from Acapulco to Mexico City. From there, the merchandise would be distributed to Veracruz where it would become part of the Indian fleet bound for Seville, and consequently the rest of Spain and the Spanish crown’s European possessions. Mexico City Travellers and writers from the 16th and 17th centuries, describe Mexico as home to some of the most luxurious cities in the world. Tales abound of wealthy men ostentatiously decorating the bands of their hats with pearls and gems, and for ladies to be splendidly decked out in rich silks and fine jewellery. Even among the disadvantaged population it was common for people to wear silk clothes

As soon as the trade route took off many Asians began to settle in Mexico, particularly Chinese and Filipinos. Many were sailors from the galleons, others were servants, while others arrived as slaves. There were probably well over 100,000 people from East Asia who started new lives by relocating to New Spain during this period The birth of Parián: the world’s first Chinatown. The world’s first Chinatown outside Asia was established in the Mexican city of Plaza Mayor as a copy of Manila’s Parián. It had a thriving marketplace with many stalls and kiosks where Chinese vendors sold Asian goods, at competitive prices. Customers could discover fine Chinese porcelain, diamonds, ivory, fabrics from China and other Asian countries, rubies, emeralds, spices from the Moluccas and many other exotic Asian goods.

The Parian, Mexico City The first global currency Manila became the central hub for trade routes linking Asia to the rest of the world, stimulating rapid international economic growth. China’s acceptance of silver in exchange for commodities such as tea, silks and ceramics would eventually result in the Spanish dollar – silver minted coins – evolving into the world’s first common currency.

At first the Chinese insisted on trading with bullion and would not accept payment for their goods in foreign currencies. It wasn’t until later that they started using the monetary unit of the Real of Eight. Pieces of Eight In 1728 new laws and regulations standardised the coinage of the Real de a Ocho, also known as the Eight Royals Coin or Pieces of Eight, as well as the Spanish dollar. The weight was reduced and the quality improved, making the dollar ideal as a common currency. One of the improvements was the addition of a striated pattern around the edge of the coin. Any chipping, a common practice at the time, was easy to identify and the coins became harder to forge Countries begin creating their own currencies based on the Spanish pieces of eight:

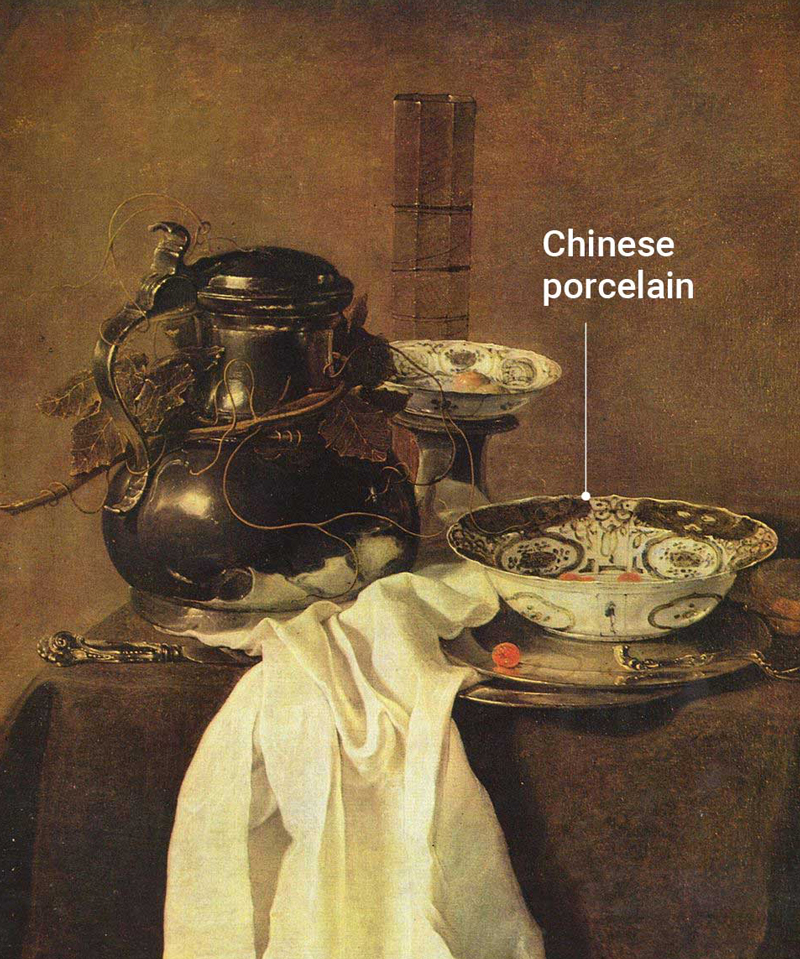

1537-1869: Spanish silver dollar Millions of coins are minted, spreading through Spain, the Americas and Southeast Asia. The consistent weight and purity sets the world standard Cultural and social legacy Just as trading goods for silver initiated economic bonds between Asia, Americas and Europe, the movement of people between continents would also lead to cultural and social exchanges. The 200 years of financial and cultural exchange which followed is now considered to be history’s first true globalisation Porcelain One of the most popular exports to New Spain and Europe was Chinese blue and white porcelain. In a 2016 archaeological excavation in Acapulco more than 3,000 pieces were found, demonstrating the kind of demand there was for this tableware. One of the characteristics of these pieces is that they were created exclusively by Chinese manufacturers for export to the American (or Western) market. These creations mixed Christian and Western elements as well as Oriental themes in the painted decorations. The pots from which people drank chocolate, then the height of fashion, were all made in China

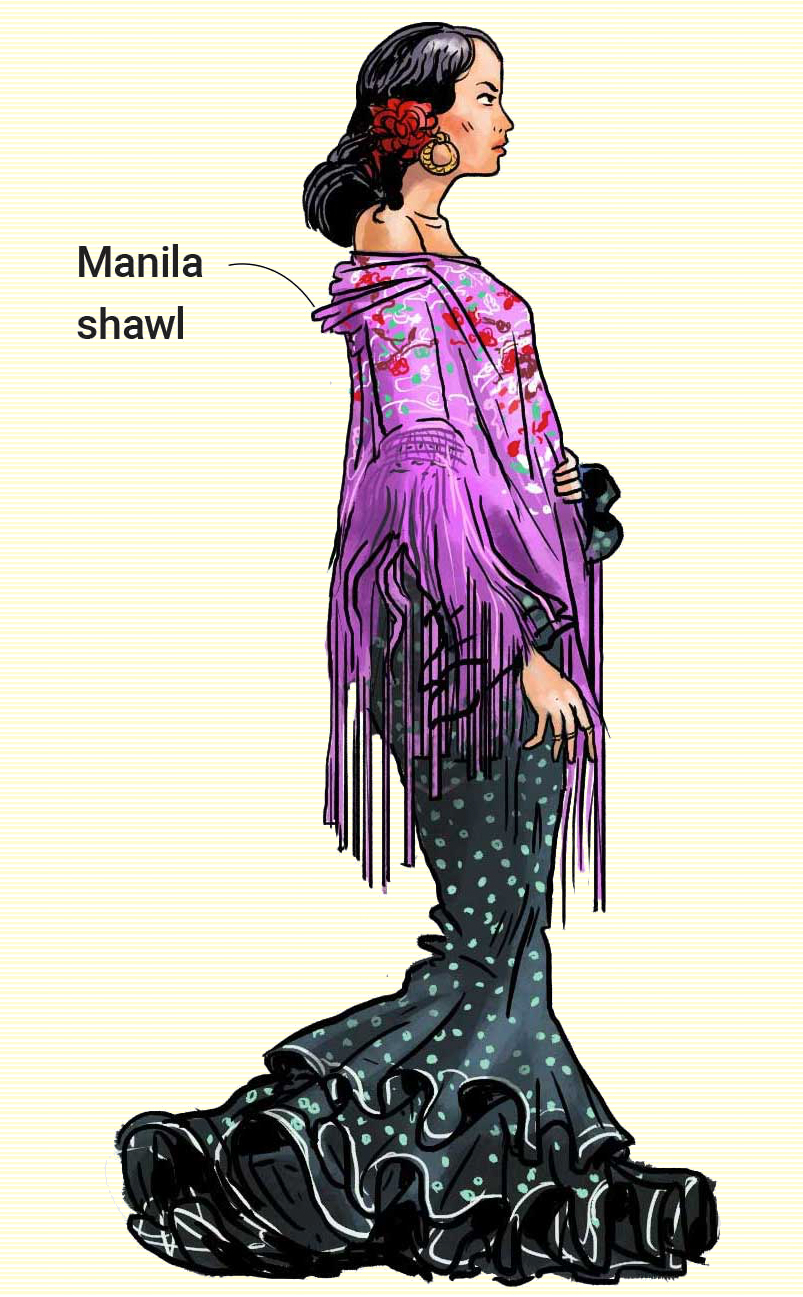

Dutch 17th-century still-life painting by Jan Jansz. Treck, showing late Ming blue and white porcelain export bowls, 1649 Also this porcelain had a huge influence on the local artisans in Mexico, who took the Chinese blue and white characteristics and translated it with their own styles and designs. An example is the porcelain from Puebla The Manila shawl Chinese fabrics were highly prized. Among the many textile products that came to the Americas and Europe was a square cloth made from silk and finely embroidered. The shawl was folded in half like a triangle and worn over women’s shoulders. This shawl became known as the manton de Manila, although it was produced in Canton not the Philippines The shawls became very popular in Spain and Spanish America. Over the years they became fashionable throughout Europe, especially in 19th century Paris. Manila shawls are still popular today and are considered to be an integral part of Spanish culture, having even been incorporated into flamenco, the quintessential Spanish art-form  Currently this garment of Cantonese origin is a must-have for flamenco dancers This shawls became very popular in Spain and Spanish America. Over the years they became fashionable throughout Europe especially in nineteenth century Paris. Their popularity is such that today, Manila shawls are considered an integral part of Spanish culture and continues to be worn.

First University in Asia Asia’s oldest operational university was established in Manila in 1611. The University of Santo Tomas remains one of the region’s top universities

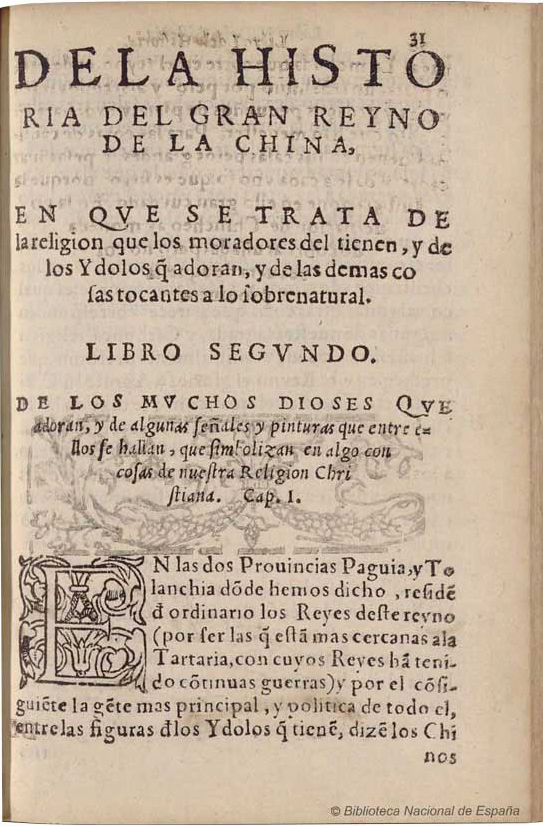

Literature interchange 1586 The Augustinian friar, Juan Gonzalez de Mendoza, wrote one of the earliest Western histories of China, Historia de las cosas más notables, ritos y costumbres del gran reyno de la China(The History of the Great and Mighty Kingdom of China and the Situation Thereof). Two years after it was published in Barcelona, the book was translated into English by Robert Parker

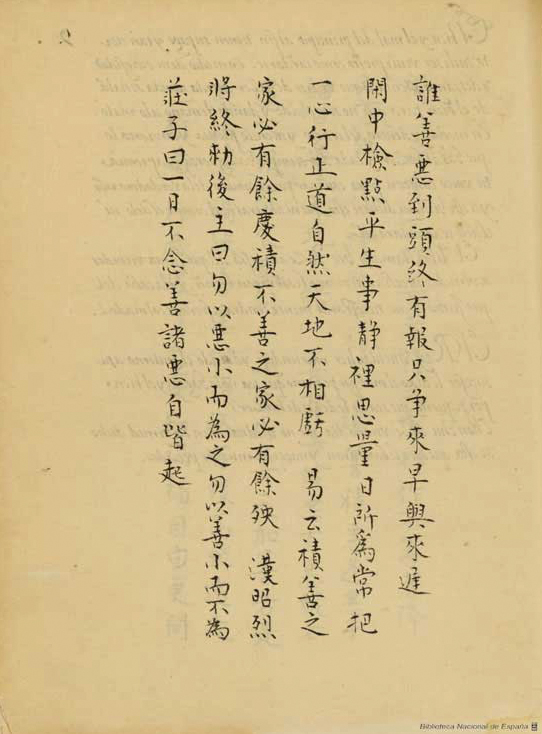

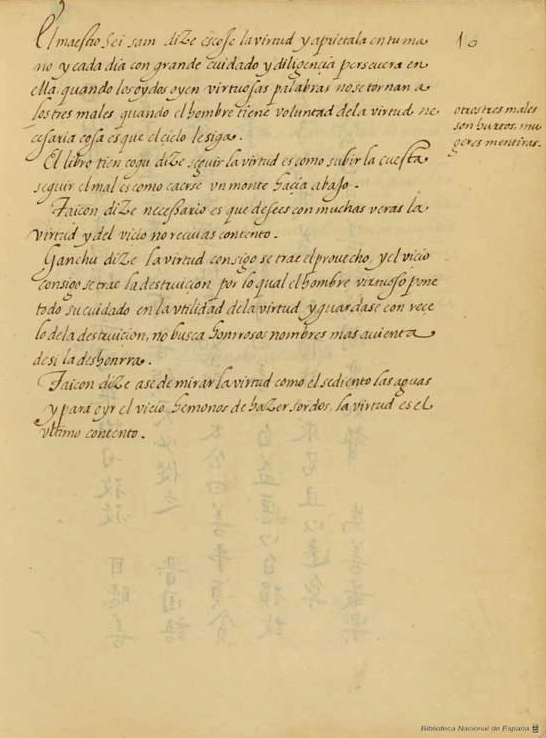

Inside page from this book printed in 1586 First translation of a classical Chinese text into a European language 1590 The Chinese book ‘Beng Sim Po Cam’ which means Rich mirror of the clear heart, or Riches and mirror with which it is enriched, and where one can see the clear and clean heart was translated into Spanish by Fray Juan Cobo around 1590 and printed in Manila in 159   Beng Sim Po Cam was published in a bilingual version

Two spread pages of the boook conserved in the National Library of Spain in Madrid Keichō Embassy mission In the years 1613 through 1620, Hasekura Tsunenaga, a Japanese samurai, headed a diplomatic mission to Spain and the Vatican in Rome. He travelled through New Spain, arriving in Acapulco and departing from Veracruz, and made various ports of call throughout Europe. On his return voyage, Hasekura and his companions retraced their route across New Spain in 1619, sailing from Acapulco for Manila, and then sailing north to Japan in 1620. He is considered the first Japanese ambassador to the Americas and Spain  THE ENDof the fourth and final chapter of “The China Ship”South China Morning Post special feature by: Special acknowledgmentsTo the writers of “The Silver Way”, Juan José Morales and Peter Gordon for their invaluable help and advice for this project SourcesThe Silver Way —Peter Gordon and Juan José Morales;

|

Send this article to a friend:

|

|

|