Collapse of the Real-Estate “Tech” IPO & SPAC Stocks: House Flippers Opendoor & Redfin Come Unglued, after Zillow

Wolf Richter

“Tech” real-estate broker Compass and “tech” renters-insurance-seller Lemonade collapsed too. All eyes on “tech” mortgage-broker Better.com’s delayed SPAC deal. I can’t wait. “Tech” real-estate broker Compass and “tech” renters-insurance-seller Lemonade collapsed too. All eyes on “tech” mortgage-broker Better.com’s delayed SPAC deal. I can’t wait.

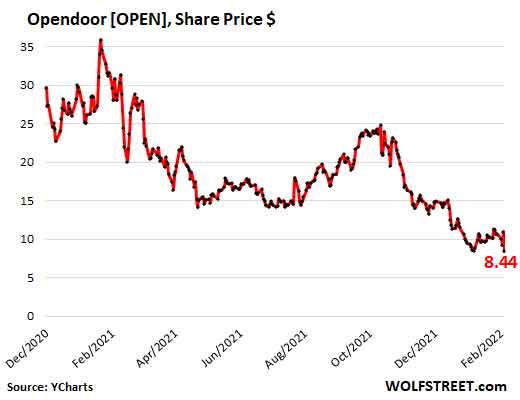

Even on Glorious Friday, the second day of a big rally after five days of sharp declines, the shares of a real-estate “tech” stock, house-flipper Opendoor, collapsed 23%, after having already collapsed in the months before.

Opendoor Technologies [OPEN], on Thursday evening, had reported a loss of $191 million for Q4, which brought its net loss for the year 2021 to $662 million, which brought its total losses for the four years that have been publicly disclosed to $1.5 billion. How can a house flipper lose $1.5 billion in four years? I don’t know either. But it isn’t over yet. And the company ended the year with an inventory of 17,009 unsold houses.

Opendoor went public in December 2020, at the IPO price of $31.47 amid enormous hoopla. By February 2021, shares had reached $39. If “February 2021” sounds familiar, it’s because that’s the month the stock market started coming unglued beneath the surface as highfliers started collapsing one at a time, each on its own schedule. The damage was such that I started reporting on it in May 2021. And this is just another chapter as it just keeps getting worse. On Friday, she shares closed at $8.44, down 78% from the February 2021 peak and 73% below its IPO price (data via YCharts):

Opendoor reported that it purchased 36,908 houses in 2021 but sold only 21,725 houses (for $8 billion) during the year, leaving it with 17,009 unsold homes ($6.1 billion) in inventory.

Opendoor financed this inventory with $6.1 billion in “non-recourse” debt backed by its houses. Non-recourse means if Opendoor defaults, its lenders get the house and cannot go after Opendoor’s other assets. If Opendoor cannot sell those homes and pay off the debt with the proceeds, it can hand the properties to the lenders and let them worry about selling the homes.

In addition, Opendoor was under contract to purchase 5,411 more homes for $1.9 billion.

About two-thirds of these 17,009 homes are finished and ready for resale. About one-third (about 5,500 homes) are “work-in-process” and are not for sale. Any of these 17,000 homes that haven’t been listed for sale, including all of the 5,500 homes that are work-in-process, are in the unknown pile of vacant homes that don’t show up in the official “supply” of homes and that don’t show up as vacant homes either.

Zillow did the same thing with a big portion of its 7,000 homes that were stuck in the pipeline before it quit the business last November and sold those homes mostly to institutional investors, who’re now trying to figure out what to do with them. These homes that are stuck in the house-flipper pipeline and that are shuffled around are vacant, but don’t show up as vacant, and they are not for sale, and don’t show up as “supply.”

House-flipping is easy – the first part, buying the house, when money is no objective, and your algo can spend as much as it wants. The rest is hard, and making money at it is even harder, especially if you overpaid in the first place. The activity is not suited for people who write algos, it turns out.

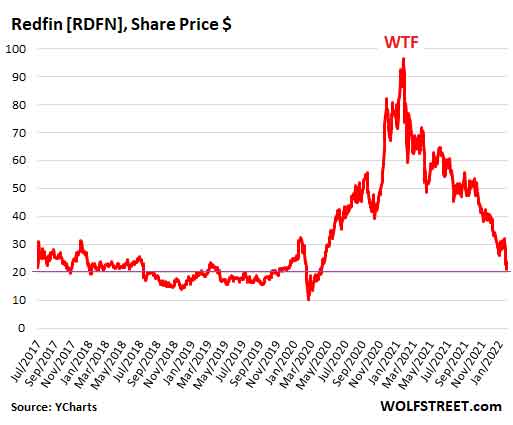

Redfin, originally an online real estate broker, also rode up the algo-based house-flipper craze starting in 2020. And its shares [RDFN] rocketed higher amid endless hoopla by the crazed crowd of stock jockeys and hit a high of $98.44 in February 2021 – yup, that February again.

Then shares began their long collapse. On Friday, they closed at $21.83, having collapsed by 78% in one year. They’re now below where they’d been after the first day of trading following its IPO in July 2017:

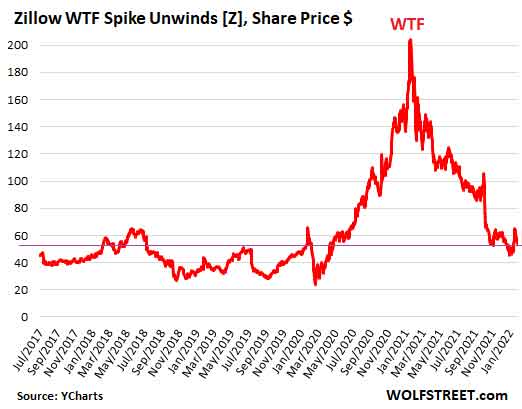

Zillow [ZG] had a brief respite in its collapse when it announced on February 10 that it lost $881 million in 2021 on its home-flipping escapade, which came unglued in November 2021, when it disclosed that it would lay off 25% of its staff and get out of the house-flipping business, and dump the 7,000 homes it had bought.

Later it disclosed that it had sold most of these houses to institutional investors – rather than to people who might have wanted to live in them. Until those vacant houses are listed for sale they don’t show up in the official “supply,” and many of them may eventually show up on the rental market. And while all this is going on as they’re being shuffled around, they don’t show up as vacant either.

The $881 million loss was less than feared, and shares bounced magically over the following three trading days, but have since then given up a portion of it. On Friday, shares closed at $57.95, down 73% from their high a year ago, and about level with where they’d been in February 2020 before the crash:

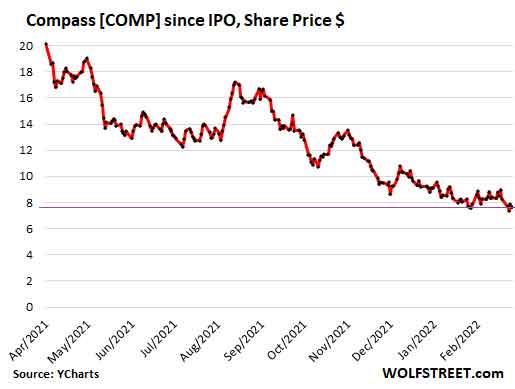

Compass, a real-estate broker that calls itself “a tech company reinventing the space,” is one of those examples – one of very many – when you realize something is seriously wrong with Wall Street. But OK, people have fun with their trading apps, and if they get cleaned out, so be it.

Compass grew by using Softbank’s money, and the money of other investors, to buy up real estate brokerages around the country. Over the five years of publicly disclosed financial statements, Compass has lost $1.44 billion. How can a real estate broker in the red-hottest no-questions-asked housing market lose $1.44 billion? That was a rhetorical question.

Compass shares [COMP] peaked on their first day of trading, following the IPO in April last year, at $22.11 and have declined ever since. On Friday, they closed at $7.65, having plunged 65% in 10 months since the high on the first day of trading, and are now 58% below the IPO price of $18 a share:

Lemonade [LMND], which is hyped as an “insurance tech company” and sells insurance for renters, homeowners, pet owners, etc., went public in July 2020 at $29 a share and in the first day of trading, amid immense hoopla, spiked 139%. It then continued spiking until it reached $182 in January 2021. And then came said February 2021, when this whole show started unraveling.

On Friday, shares closed at $23.48, down 83% from the high, and 19% below the IPO price at which the shares never even traded because the first trade was at $50 a share, causing the tech stock pundits to lament how the company “mispriced” the IPO and how much money it “left on the table.” Yup, that’s how crazy this show was at the time.

Waiting for a share-price collapse is Better.com, a “tech” mortgage lender, backed by Softbank. It’s not yet a publicly traded stock because its merger with a SPAC was postponed in December 2021 after the CEO fired 900 employees, most of them in India, via a Zoom meeting that went viral, that idiot.

With the SPAC merger, and therefore the inflow of cash, having been delayed, the company raised $750 million from Softbank and its SPAC backers because, you know, these kinds of companies constantly burn large amounts of cash and constantly need new cash to burn.

So I’m looking forward to the moment the stock finally starts trading so I can add it to this list of collapsing real-estate “tech” stocks. This should be a goodie. So let’s hope that the merger with the SPAC goes through.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? Using ad blockers – I totally get why – but want to support the site? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified via email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Sign up here.

Founder, Wolf Street Corp, publisher of WOLF STREET. Founder, Wolf Street Corp, publisher of WOLF STREET.

In his cynical, tongue-in-cheek manner, he muses on WOLF STREET about economic, business, and financial issues, Wall Street shenanigans, complex entanglements, and other things, debacles, and opportunities that catch his eye in the US, Europe, Japan, and occasionally China.

Wolf lives in San Francisco. He has over twenty years of C-level operations experience, including turnarounds and a VC-funded startup. He has a BA, MA, and MBA (UT at Austin).

In his prior life, he worked in Texas and Oklahoma, including a decade as General Manager and COO of a large Ford dealership and its subsidiaries. But one day, he quit and went to France for seven weeks to open himself up to new possibilities, which degenerated into a life-altering three-year journey across 100 countries on all continents, much of it overland, that almost swallowed him up.

wolfstreet.com

|

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/images/live/s_gold.gif)

![[Most Recent USD from www.kitco.com]](http://www.weblinks247.com/indexes/idx24_usd_en_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/images/live/s_silv.gif)