Democracy In The Madhouse

Darryl Robert Schoon

As we approach the 2018 US midterms, interest in voting is the highest it’s been in decades. Republicans, Democrats, independents and even the disaffected are engaged; and with voting 10 days away, we should review democracy’s origins as it relates to the outcome of the midterms. As we approach the 2018 US midterms, interest in voting is the highest it’s been in decades. Republicans, Democrats, independents and even the disaffected are engaged; and with voting 10 days away, we should review democracy’s origins as it relates to the outcome of the midterms.

The success of self-government ultimately depends on the nature of the self to be governed.

Historians believe the earliest example of democracy occurred in India during the 6th century B.C. There is, however, an earlier example, the story of which was lost for centuries and only recently rediscovered.

In the 7th century B.C., democracy made its unexpected debut in Muktabar at its infamous madhouse. Located in Asia Minor in what would have been Ubiquistan and later assimilated into what is now Afghanistan and portions of Tibet, Muktabar was best known for its madhouse, a most unlikely locale for the world’s earliest appearance of democracy, a process now believed to be a solution for the world’s ills.

Remote even for that part of the world, it was perhaps why Muktabar was chosen to be the location of the madhouse. Although remote, due to unique geographical factors Muktabar was blessed with a relatively mild climate and an abundance of water.

This made it possible for the madhouse to be self-sustaining, requiring only a minimal amount of attention and even less supervision. The necessity to survive, rather than being an insurmountable obstacle, was instead a natural inducement for the inmates to eke out an existence in that remote area. The madhouse of Muktabar was perhaps the world’s first out-patient clinic.

Not understanding why they were there, the inmates of the madhouse surmised the gods were responsible. After all, there was shelter and enough tools and resources available that the ambulatory among them could recognize that such had been left for their personal use.

Rudimentary and spontaneous rituals of thanksgiving to the gods were then organized. Shortly thereafter, these rituals became institutionalized and all were required to partake and give personal thanksgiving, even those who had not the awareness and capacity to do so.

This required ritualization became the basis of the earliest form of government and religion at the madhouse. This form was not the democratic process which was to come later. The earliest form of order at the madhouse was tyranny.

Those who organized the rituals of thanksgiving discovered by so doing they had achieved power over others; and, it was the awareness of this power that led to the tyranny that followed.

We make no judgment as to what occurred. All those at Muktabar were mad to a greater or lesser degree, and therefore not responsible for what they did. Nonetheless, the tyranny of those who assumed control increased until it became unbearable for the rest of those confined.

Those who ruled the madhouse claimed they ruled on the behalf of the gods. Because the inmates were mad and had no way of knowing otherwise, they accepted this assertion as true until the oppression became so great, they rebelled.

Force was used to put down the uprising and then maintained to insure order. Since those who controlled the madhouse had access to supplies and controlled the distribution of food, they paid the larger and more violent madmen to enforce their increasingly dictatorial demands. That the first police state occurred in the very place where democracy was to arise is perhaps ironic; but, then again, perhaps it is not.

The use of violence restored order but because human nature, mad or not, knows no bounds, the resumption of order caused those who governed badly to behave even more badly; and, now faced with opposition, their tyrannical demands multiplied as did their punishments.

What actually occurred at the madhouse is not known. However, it can be assumed that it was both brutal and selfish in the extreme. The oppressed had no recourse. The towns and cities where they were from were glad to be rid of them and chose not to intervene, no matter how egregious the reported crimes.

But there comes a time when too much is too much, and fear of retribution is accepted as the price to be paid in order to end a life of continuing servitude and cruelty; and, thus, revolution came to the madhouse of Muktabar and after revolution came democracy.

Self-rule, the democratic process, was a new and unexpected experience. Those at the madhouse did not know it was the first such instance in history. It seemed at the time the natural thing to do — and it was.

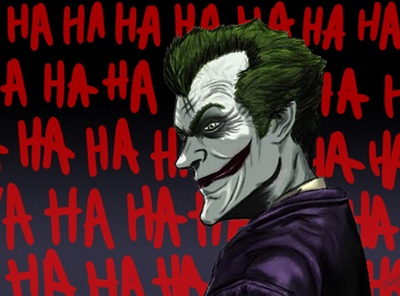

In the beginning, the inmates found self-rule to be exhilarating. But in the end, they found themselves increasingly unhappy with their choices. When crazy people vote, their choices reflect their madness. This was true at the madhouse of Muktabar — it is also true today.

Darryl Robert Schoon

Darryl Robert Schoon writes and lectures on the causes and significance of the economic collapse. His book, Time of the Vulture: How to Survive the Crisis and Prosper in the Process predicted the collapse and the following severe downturn. He graduated from UC Davis (1966) in political science with a focus on East Asia. His immersion in the 1960’s subculture in the Haight-Ashbury radically altered his outlook contributing to the unique point-of-view through which he views the collapse of the present economic system. He has lectured in Europe, Australia and the US and has written five books. Visit his website at www.drschoon.com. You can reach Darryl at: [email protected].

www.drschoon.com

|

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/charts/metals/gold/t24_au_en_usoz_2.gif)

![[Most Recent USD from www.kitco.com]](http://www.weblinks247.com/indexes/idx24_usd_en_2.gif)

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/charts/metals/silver/t24_ag_en_usoz_2.gif)